What the new newsletters can learn from the early days of blogging

Today's newsletters look more and more like the early days of blogging - but with one missing ingredient.

The latest edition of Ian Silvera’s newsletter Future News caught my attention with its headline:

As a very long-term blogger, I’m fascinated by the similarities and differences between the new wave of independent newsletters and the emerging blogosphere of the early 2000s. Such a blunt statement that they are not the same intrigued me.

Diving into the newsletter, I found that the actual justification for that statement was only mentioned briefly, in the context of big names creating their own newsletters:

To some extent I’m onboard with Chen’s thesis: readers can now have a direct financial and editorial relationship with their favourite writers, the most recent being conservative columnist Andrew Sullivan (@SullyDish) who quit New York Magazine for Substack. But unlike the blogosphere that Sullivan helped create, there doesn’t yet seem to be a community where writers would post and share other people’s work.

This is the one critical idea that was central to early blogging that has not (yet) been widely embraced by newsletters: the sense that bloggers were a community and that the discussion was going on between them. Why did this matter? Well, for one it helped define the voice of blogging - more conversational, more discursive that traditional journalism. That seems less striking now, two decades on, because mainstream journalism has largely appropriated that tone of voice for good or (I’d argue) ill.

But the other thing it brought was discovery - the ability to find other blogs worth reading. This was an era before Twitter, Facebook or many of the tools of discovery we use now. Search — and Google in particular — did exist. And it was one way of finding new readers. But a link from another well-read blogger was the real win you hoped for.

Equally, this worked for readers, because you could quickly and easily expand your range of reading. You would have your favourites, of course, but you'd trust them to be a good filter of other writing out there.

Blogging was a social process before the phrase “social media” had been coined. But newsletters are still adopting a much more traditional media approach, acting as micro-publications with little awareness of others.

Create your newsletter neighbourhood

This is a basic growth strategy any newsletter writer could adopt right now. Stop thinking of your missive as something that exists in isolation, but acknowledge and link to the places that you’ve drawn ideas from - or with whom you disagree.

Certainly, if you’re an independent journalist creating a newsletter, it’s worth finding a group of peers, who make an effort to interlink between each other. Why? Because that interlinking is the rising tide that floats all boats.

The biggest challenge for email newsletters as a product in the own right is discovery. Newsletters that are part of a wide publication can gain subscribers that way. Their aim is slightly different - it’s to boost engagement with an existing user base, rather than being a product in its own right.

If you’re just selling a newsletter, you’re highly reliant on constant plugs via social media, and recommendations from readers. A group of newsletter writers who are discussing related subjects have the potential to boost subscriptions right across the range, by interlinking. That’s why most newsletter platforms have a web presence - you can direct people towards a web-accessible version of the same content: it facilitates linking (as I’ve done to Silvera’s Substack newsletter above), as well as people discovering you via search.

The ported audience

Many of the “big names” who have started newsletters are merely coasting on the audience that their employers have gifted them. Build a name on a major publication, and then head off to create your own newsletter.

The problem with that is is that you need a path to replace the readers that churn out. Not everyone will stay subscribed, as as your old platform fades, you need to find ways of drawing in new people.

As Silvera puts it:

That is probably why there are currently no ‘Substack stars’ since many high-profile journalists have simply lifted their followings from other platforms and outlets onto the network.

Finding ways of growing newsletter audiences is likely to become a big battleground in the coming months. In fact, it may have already started.

Email growth hacking

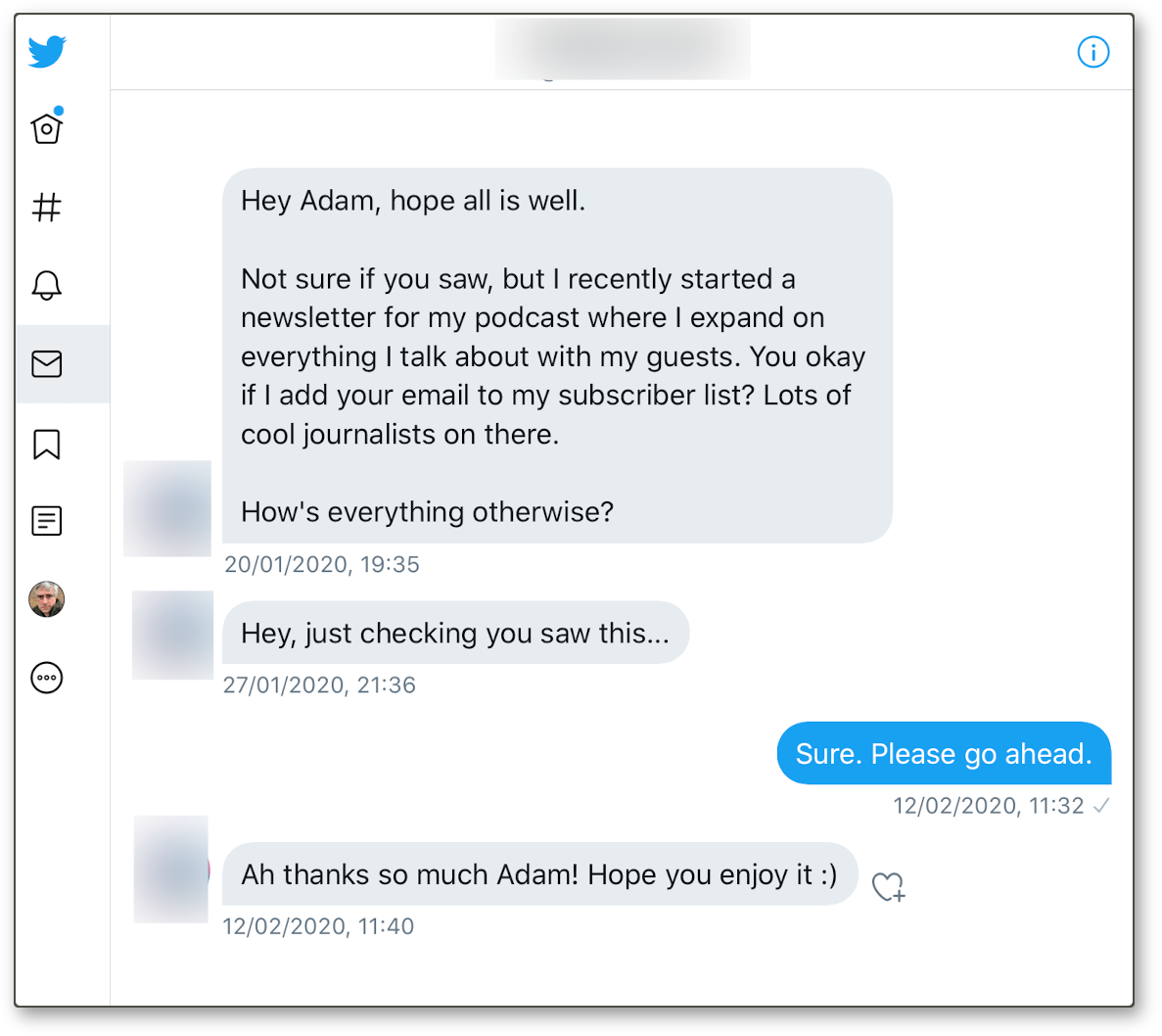

There is at least one writer of a media newsletter who is “growth-hacking” by following people on Twitter, DMing them a stock message asking permission to subscribe them to the newsletter:

I confess, as you can see, I fell for this. I was only alerted to the issue by a tweet from former Times newsletter head Joseph Stashko:

Lol. A journalist with 10k followers followed me, dm-ed me this, then unfollowed when I didn’t reply. Big up pic.twitter.com/WKv4aXszxz

— Joseph 🇺🇦 (@JosephStash) June 29, 2020

If you follow the Twitter thread, you can see that a lot of journalists have had the same. It may be growing our growth-hacking journalist's list - but it’s slowly destroying his reputation, too.

(He's followed and unfollowed me a couple of times in the last few weeks, since I realised what he was doing and unsubscribed/unfollowed him everywhere. He's clearly using an automated service of some sort to manage this…)

All of which brings us back to the start. The element missing from newsletters right now is a sense of community, of a group of people exploring a topic together. And if you want to know what that looks like - well, this post is, itself, part of a dialogue between Silvera’s newsletter and my “blogletter”.

Will we see more people follow this path?

Lovely Links

📧 A list of 80 single person newsletters that might interest you

💸 Reporters are leaving newsrooms for newsletters.

😡 Publishers are not delighted about this. This may yet become a battleground.

Hello! Thanks for reading. If you found this useful or interesting, you can get updates and exclusive, member-only analysis delivered direct to your mailbox by signing up for the newsletter.

Sign up for e-mail updates

Join the newsletter to receive the latest posts in your inbox.